Hayden's Armida

Armida was the last opera Haydn created for the opulent surroundings of the Eszterhazy Palace, where it received a phenomenal 54 performances; Haydn himself judged it his best opera.

Pinchgut was proud to bring this masterpiece to the stage in 2016.

REVIEWS

READ

1] Joseph Haydn

Of humble origins, Franz Joseph Haydn (March 31, 1732 - May 31, 1809) was born in the village of Rohrau, near Vienna. When he was eight years old he was accepted into the choir school of Saint Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna, where he received his only formal education. Dismissed from the choir at the age of 17, he spent the next several years as a struggling free-lance musician.

He studied on his own the standard textbooks on counterpoint and took occasional lessons from the noted Italian singing master and composer Nicola Porpora. In 1755 Haydn was engaged briefly by Baron Karl Josef von Furnberg, for whom he apparently composed his first string quartets. A more substantial position followed in 1759, when he was hired as music director by Count Ferdinand Maximilian von Morzin. Haydn's marriage in 1760 to Maria Anna Keller proved to be unhappy as well as childless.

The turning point in Haydn's fortunes came in 1761, when he was appointed assistant music director to Prince Pal Antál Esterházy; he became full director, or Kapellmeister, in 1762. Haydn served under the patronage of three successive princes of the Esterházy family. The second of these, Pal Antál's brother, Prince Miklós Jozsef Esterházy, was an ardent, cultivated music lover. At Esterháza, his vast summer estate, Prince Miklós could boast a musical establishment second to none, the management of which made immense demands on its director. In addition to the symphonies, operas, marionette operettas, masses, chamber pieces, and dance music that Haydn was expected to compose for the prince's entertainment, he was required to rehearse and conduct performances of his own and others' works, coach singers, maintain the instrument collection and music library, perform as organist, violist, and violinist when needed, and settle disputes among the musicians in his charge. Although he frequently regretted the burdens of his job and the isolation of Esterháza, Haydn's position was enviable by 18th-century standards. One remarkable aspect of his contract after 1779 was the freedom to sell his music to publishers and to accept commissions. As a result, much of Haydn's work in the 1780s reached beyond the guests at Esterháza to a far wider audience, and his fame spread accordingly.

After the death of Prince Miklós in 1790, his son, Prince Antál, greatly reduced the Esterházy musical establishment. Although Haydn retained his title of Kapellmeister, he was at last free to travel beyond the environs of Vienna. The enterprising British violinist and impresario Johann Peter Salomon lost no time in engaging the composer for his concert series in London. Haydn's two trips to England for these concerts, in 1791-92 and 1794-95, were the occasion of the huge success of his last symphonies. Known as the "Salomon" or "London" symphonies, they include several of his most popular works: "Surprise" (#94), "Military" (#100), "Clock" (#101), "Drum Roll" (#103), and "London" (#104).

In his late years in Vienna, Haydn turned to writing masses and composed his great oratorios, The Creation (1798) and The Seasons (1801). From this period also comes his Emperor's Hymn (1797), which later became the Austrian national anthem. He died in Vienna, on May 31, 1809, a famous and wealthy man.

Haydn was prolific in nearly all genres, vocal and instrumental, sacred and secular. Many of his works were unknown beyond the walls of Esterháza, most notably the 125 trios and other assorted pieces featuring the baryton, a hybrid string instrument played by Prince Miklós. Most of Haydn's 19 operas and marionette operettas were written to accommodate the talents of the Esterháza company as well as the tastes of his prince. Haydn freely admitted the superiority of the operas of his young friend Wolfgang Mozart. In other categories, however, his works circulated widely, and his influence was profound. The 107 symphonies and 68 string quartets that span his career are proof of his ever-fresh approach to thematic materials and form, as well as of his mastery of instrumentation. His 62 piano sonatas and 43 piano trios document a growth from the easy elegance suitable for the home music making of amateurs to the public virtuosity of his late works.

Haydn's productivity is matched by his inexhaustible originality. His manner of turning a simple tune or motive into unexpectedly complex developments was admired by his contemporaries as innovative. Dramatic surprise, often turned to humorous effect, is characteristic of his style, as is a fondness for folkloric melodies. A writer of Haydn's day described the special appeal of his music as "popular artistry", and indeed his balance of directness and bold experiment transformed instrumental expression in the 18th century.

2] The Story

To prevent the capture of Jerusalem by the knights of the First Crusade, The Prince of Darkness has sent the enchantress Armida into the world to seduce the Christian heroes and turn them from their duty. The bravest of these, Rinaldo, has fallen under Armida's spell. She comes to love him so deeply that she cannot bring herself to destroy him.

Act 1

Scene 1: A council chamber in the royal palace of Damascus. King Idreno is alarmed that the crusaders have crossed the Jordan River. The heathen sorceress Armida seems to have triumphed over the crusaders, but fears that her conquest is not complete without gaining the love of the Christian knight Rinaldo. Now Rinaldo is obsessed with Armida and promises to fight against his fellow Christians, if victorious King Idreno offers him the kingdom and Armida’s hand. Armida prays for Rinaldo’s safety.

Scene 2: A steep mountain, with Armida's fortress at the top. The knights Ubaldo and Clotarco plan to free Rinaldo from Armida’s clutches. Idreno sends Zelmira, the daughter of the sultan of Egypt, to ensnare the Christians but on encountering Clotarco she falls in love with him and offers to lead him to safety.

Scene 3: Armida's apartments. Rinaldo admires the bravery of the approaching knights. Ubaldo warns Rinaldo to beware Armida's charms, and reproaches the dereliction of his duty as a Christian. Although remorseful, Rinaldo is unable to escape Armida's enchantment.

Act 2

Scene 1: A garden in Armida's palace. Zelmira fails to dissuade Idreno from planning an ambush of the crusaders. Idreno pretends to agree to Clotarco's demand that the Christian knights enchanted by Armida be freed. Reluctantly, Rinaldo leaves with Ubaldo. Armida expresses her fury.

Scene 2: The crusader camp. Ubaldo welcomes Rinaldo, who prepares to go into battle. Armida begs for refuge and Rinaldo’s love. Rinaldo departs for battle with Ubaldo and the other soldiers.

Act 3

Scene 1: A dark, forbidding grove, with a large myrtle tree. Rinaldo, knowing that the tree holds the secret of Armida’s powers, enters the wood intending to cut it down. Zelmira appears with a group of nymphs, and they try to get him to return to Armida. As he is about to strike the myrtle, Armida, dishevelled, appears from it and confronts him. Armida cannot bring herself to kill him; Rinaldo strikes the tree and the magic wood vanishes.

Scene 2: The crusader camp. The crusaders prepare for battle against the Saracens. Armida appears, swearing to pursue Rinaldo everywhere. As Rinaldo moves off, she sends an infernal chariot after Rinaldo.

3] About Armida

Not only is Armida Haydn’s most highly regarded opera, but the composer himself, on completing the score in 1783, referred to it as his best work.

Armida was written for Count Nikolaus Eszterházy’s palace theatre in Hungary and first performed there, with spectacular success, on 26 February 1784. Between 1784 and the theatre’s closure in 1790, it received a total of fifty-four performances, and was also staged in Vienna (1791), Preßburg (1786), Budapest (1797) and Turin (1804).

The score itself was not published until 1965 (as part of the complete Haydn edition), and the Wrst modern performances (a concert version for Cologne radio, followed by a fully staged performance in Berne) took place three years later. The Haydn Festival in Eisenstadt gave notable performances during its 2001 season, and in 2007 Armida was one of the most important opera productions at the Salzburg Festival.

An Italian dramma eroico loosely based on an epic poem by Torquato Tasso, Armida is set at the time of the Crusades. Its theme is the superior call of duty over the seductive voice of love. The person at the centre of this dilemma is the crusading knight Rinaldo, who is loved by the sorceress Armida. Although it appears that love will triumph, Rinaldo succeeds in tearing himself away and Armida’s affection turns to hatred. The opera ends with the participants pondering their fate against a background of martial music.

Haydn was composing for an orchestra and musicians he knew intimately, enabling him to experiment and to create a magnificent historical spectacle for the opulent stage at Eszterháza. Yet, by eighteenth-century standards, Armida is relatively short and its resources quite modest: there is no castrato part, three of the six roles are for tenor, and, apart from a trio and the Finale, there are no ensembles. A three-part overture of exceptional colour opens the work, and the story unfolds through a series of arias, containing some of Haydn’s most inspired music, and accompanied recitatives, which skilfully convey the “psychological” conflict at the heart of the drama. The second and third acts are especially notable for their extended, through-composed final scenes, but the dramatic highlight of the whole work is undoubtedly Armida’s bravura vengeance aria in Act II. Haydn’s orchestral tone-painting in some of the more lyrical and imaginative episodes, particularly the enchanted grove scene in Act III, reveal a composer of genius at the very height of his creative powers.

4] Interesting Facts about Haydn

~ The son of a wheelwright and a local landowner's cook, Haydn had such a fine voice that at the age of five he entered the Choir School of St Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna.

~ His ethereal treble tones lasted until he was 16, a fact noticed by the Habsburg Empress, Maria Theresa, who uttered her famous criticism: "That boy doesn't sing, he crows!".

~ Haydn left the choir in memorable fashion - snipping off the pigtail of one his fellow choirboys - and was publicly caned.

5] Other Armida Operas

Chrisian soldier fighting in the Crusades is seduced by an Arab sorceress. The choice he has to make is an age-old one: Stay or go? Love or duty? Drawn from a popular Italian epic, the story of Armida is simple. In the 17th and 18th centuries it inspired a burst of fascinatingly different operas by Lully, Handel, Vivaldi, Jommelli, Salieri, Sacchini, Gluck and Haydn, to name just a few. Rossini’s propulsively tuneful take on the story bowed in 1817, Dvorak’s Wagnerian one in 1904.

For a long time these works went largely unseen, casualties of a period during which Baroque, classical and bel canto operas had fallen out of favor. Gluck’s “Armide,” written in French, had seven Metropolitan Opera performances from 1910 to 1912, and that was all.

Differing both in broad plot points and small details, the operas are all based on an episode from Torquato Tasso’s epic poem “Gerusalemme Liberata,” first published in 1581. Tasso had been influenced by Ariosto’s “Orlando Furioso,” another fantastical epic about love’s travails during a clash of West and East, which had appeared to acclaim in several versions in the 16th century.

The many readers of Ariosto and Tasso were no doubt drawn to the stories’ magical trappings. Both poems are full of enchanted gardens, sea monsters and even, in “Orlando Furioso,” a trip to the moon. And they were certainly getting a juicy romance, complete with agonized paramours, abandonment and rage.

But what they were reading, in the guise of a love story with special effects, was something deeper: nothing less than a foundational narrative of modern Western culture. Tasso’s poem and the operas it inspired are commemorations of the defeat of the East (the slippery Armida) and the establishment of a rational, clear-headed West (the bravely resistant Rinaldo) rising from the ashes of the Dark Ages.

In the various versions of “Armida” the East represents guile, laxity and confusion: every force opposing reason and progress. “Love detains me, my honor summons me,” Rinaldo sings in Haydn’s version, neatly describing his predicament. When he finally decides he must return to his fellow soldiers, his explanation is that “reason must triumph.”

Honor is here seen as synonymous with decisiveness and forward-thinking clarity, while love is sluggish and nostalgic, dragging its victims into the past. It is telling that in Philippe Quinault’s libretto, used by both Lully and Gluck, the illusions spun to trap Renaud’s (the French Rinaldo’s) fellow soldiers take the form of their past loves.

The Tasso adaptations follow the opposite of the classic Romantic narrative, the Wagnerian valorization of a love capable of redeeming a broken world. In these operas a fragile world manages just barely to dodge the snares of love. Perhaps the most surprising thing about the various versions of “Armida” is how vulnerably they depict the men of the West, how anxious the works’ creators are about masculine stability. The civilization the Christian soldiers represent — the civilization we are part of — is, in these tellings, perpetually on the verge of collapse or capitulation. The music is beautiful but the message is ominous.

Quinault’s 1686 take on the story complicates matters by creating a nuanced title character. His Armide is aggressive and hateful but also damaged and pained, prone to the same illusions and doubts she inspires in others. As with the characters in his and Lully’s masterpiece, “Atys,” Armide’s tragedy is to be undone by love’s insidious power even as she considers herself above such a humble emotion.

Gluck’s co-opting of the “Armide” text not quite a century after Lully, with only limited changes, set off a rage for retrofitting Quinault’s librettos with new music. The genius of both Gluck and Lully is to prove in music the vulnerability that Armide refuses to allow in her words. When she bemoans that, despite herself, Renaud’s “importunate image” disturbs her rest “incessantly,” Lully makes sure we feel her susceptibility to love, even as she pretends to be free of it, in the sudden darkening of the line on “incessamment.”

In 1777, when individual numbers had begun to take on a more self-enclosed character, Gluck set Armide’s aria “La chaîne de l’hymen m’étonne” (“The bonds of marriage frighten me”) to music so floatingly beautiful that her protestation “How unhappy a heart becomes when liberty forsakes it” simply melts away. We know she’s lying to herself.

In Quinault’s version, as in Tasso, Armida is ready to kill Rinaldo before falling in love with him. But her ferocious side is barely present in Haydn’s opera, which begins comfortably later in the story, with the two lovers happily ensconced at the court of Damascus. From there the only way to go, as in Handel’s cantata “Armida Abbandonata,” is to the sadness of her being forsaken.

The result is poignant but it sacrifices the altitude from which Tasso has Armida fall. In Rossini’s version, which begins with the devious sorceress hurling dazzling coloratura lines that parallel her deceptions, the composer craftily strips away her ornaments as her helplessness is revealed. The woman who begins the opera in utter command is left moaning “Dove son io?” (“Where am I?”) before rising in a fiery chariot to seek her vengeance.

Many of the canonical operas are spectacles of female degradation, in which powerless, marginalized women grow ever more powerless and marginalized. Armida’s trajectory is far more complicated, and far more moving.

By ZACHARY WOOLFE from the NYTimes 2012

WATCH

One of Armida's most beautiful arias "Vedi se t'amo" as sung here by Joyce DiDonato.

ARTIST INFORMATION

Armida Rachelle Durkin

Rinaldo Leif Aruhn-Solén

Zelmira Janet Todd

Ubaldo Jacob Lawrence

Clotarco Brenton Spiteri

Idreno Christopher Richardson

Antony Walker, conductor

Crystal Manich, director

Alicia Clements, set designer

Christie Milton, costume designer

Matthew Marshall, lighting designer

LISTEN

BEHIND THE SCENES

Take a look behind the scenes at what goes on during rehearsals as the cast and creative time prepares for Armida

THE CREATIVE TEAM

An Introduction: We caught up with Rachelle Durkin, conductor Antony Walker and director Crystal Manich to discuss the upcoming production.

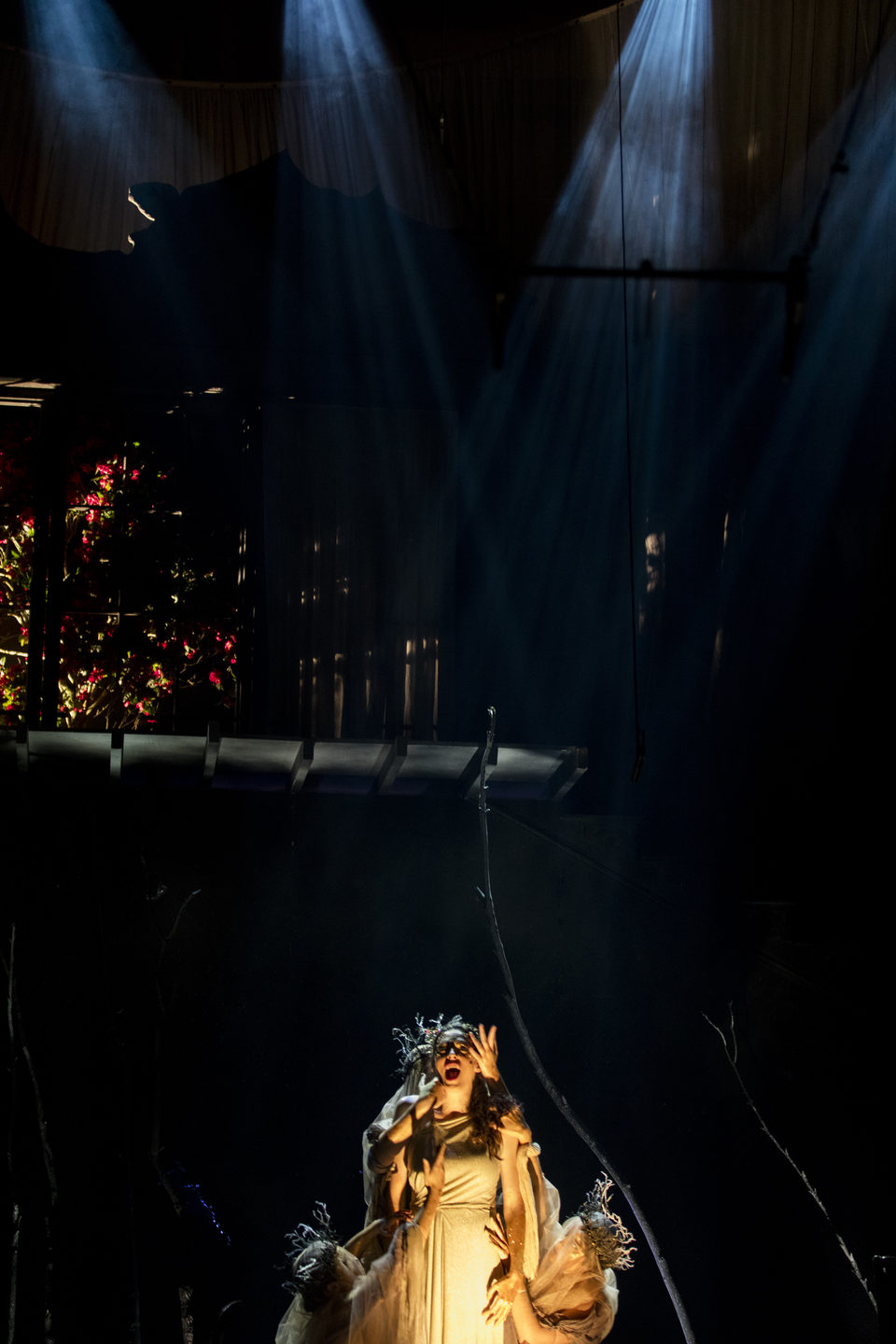

Gallery

We acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we work and perform, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation – the first storytellers and singers of songs.

We pay our respects to their elders past and present.

CONTACT

PO Box 291, Strawberry Hills, NSW, 2012, Australia

Ticketing and Customer Service 02 9037 3444 | ticketing@pinchgutopera.com.au

info@pinchgutopera.com.au

© COPYRIGHT 2002 - 2024 PINCHGUT OPERA LTD | Privacy Policy | Accessibility | Website with MOBLE