Ormindo

By Francesco Cavalli

libretto by Giovanni Faustini

Dec 2, 5, 6 & 7 2009

City Recital Hall Sydney

Cavalli's Ormindo

Not much was known about the generations of opera composers between Monteverdi and Purcell. Pinchgut has changed that with a sparkling production of Francesco Cavalli's Ormindo. A student, and later a colleague of Monteverdi's, Cavalli wrote a number of operas than began life as street entertainment and ended up in royal courts. They are at once funny, serious, emotional, gorgeous and silly with some of the most amazing music you are likely to hear.

A story of pure soap-opera, Ormindo runs the gamut of emotions. You'll be laughing then crying. With mistaken identity, visits from ghosts, fake poisons, forgotten lovers, true love and some camel humour, Ormindo is a whirlwind of delightful sounds and experiences.

REVIEWS

READ

1] Notes from the Musical Director

When opera went public in the mid-17th-century, moving from the formality of private courts to raucous theatres that were open to all, it marked the beginning of a burgeoning and prosperous industry of which Pinchgut Opera in the 21st century is a proud continuation. Impresarios, promoters, composers and singers quickly realised that opera was potentially big business. Cities such as Venice, Milan, Rome and Florence were increasingly characterised by a hub of opera houses that ourished around traditional areas of commerce. Foreigners and locals alike thrilled at the spectacles, and casinos and gambling-houses were soon to be found close to the opera houses, taking advantage of the thronging crowds. Prostitutes and fruit-sellers plied their trade in the lower levels; music connoisseurs, peering at their libretti by the light of wax tapers, sat next to the pit, the better to hear the music.

The opera box system developed fairly quickly to satisfy the needs of the audience, which did not attend to the evening’s entertainment in the reverential, absorptive silence we maintain today – a relic of late 19th-century attitudes to which we still adhere. An architectural detail sadly lost to modern society, the opera box was the perfect place to conduct business, court lovers, entertain guests and enjoy an excellent evening’s entertainment. Those desiring a little extra privacy could draw the curtains and still hear the music. Some boxes had billiard tables and wine cellars. Busy kitchens served hot food.

Although City Recital Hall Angel Place has neither boxes nor billiard tables, we hope that in tonight’s performance you will be able to imagine the thrilling experience of a 17th-century audience enthralled by a tightly-run, witty narrative delivered by star singers in an urban space of unparalleled sophistication. Although the rowdy informality has (sadly) disappeared, the music, star singers and unparalleled urban space have not. And it is to these last three elements that Pinchgut Opera’s artistic vision has been dedicated.

Pinchgut Opera has been from the beginning absolutely committed to a historically-informed approach with regard to the musical score, but our experiences have and will always be rmly rooted in the present. Antony Walker and I have continually sought to blend our historical curiosity with a performative reality honed by experience, as we seek to mount productions that reect our pragmatic spirit whilst contemplating different operatic periods and approaches. Being a part of Pinchgut Opera, whether as audience member, musician or crew, means being part of a voyage of discovery.

It’s a great pleasure to present Cavalli’s Ormindo tonight, as his operatic and dramatic approach in many ways resembles our own. By no means slavishly adhering to his own text when occasion demanded an alteration, Cavalli instead sought to highlight, with rare musical intelligence, the dramatic intentions of his brilliant librettist, Faustini. As a great student of Monteverdi, Cavalli understood more than anyone else the importance of opera’s newfound popularity. Drama was heightened and sophisticated by the presence of music in much the same way that the lm camera transformed our sense of theatre. Musical accompaniments added psychological depth to the text, just as the skilful editing of moving pictures changed the way we perceived dramatic representations at the advent of cinema. Accomplished composers like Cavalli were able to interpret and colour their librettists’ work with subtle interactions between recitative and aria, compositional choices determined by the composer’s dramatic judgment and knowledge of his public. Cavalli’s great success and popularity during his lifetime is a testament to his genius.

Cavalli has only recently been rediscovered and reevaluated and it would be remiss of me not to mention the name of his great advocate, Raymond Leppard, who mounted productions in the late 1960s and brought Cavalli’s achievements to the attention of a broad audience. Leppard lavishly realised Cavalli’s bare-bones score for symphonic strings and a large continuo. He stated that he felt he had to thicken Cavalli’s score with his own embellishments because otherwise it would sound like a ‘child’s lesson’. In 1967 he wrote: ‘There is not sufcient music written out in [Cavalli’s scores] for them to be for more than specialised use until a performing tradition has been re-created for them.’

Luckily for us, the many advances in the playing techniques and improvisatory habits of early music performers since the 1970s and 80s have now meant that a real living, breathing performing tradition is in place. This evening’s performance will be conducted from the harpsichord, just as Cavalli did for the original production. The transparent score that Leppard thought insufcient in the late 1960s does in fact have the capability, in the right hands, to be a supple object of great expressive potential, when realised by talented singers and instrumentalists conversant with the style and performative tradition of the period, as is the case tonight.

This evening’s performance will present Cavalli and Faustini’s work at a higher pitch than most of us are familiar with. Studies of instruments have shown that Venetian pitch was stable around A=466 for much of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and we have found that adopting this pitch alleviates many of the concerns of vocal range that have plagued more recent productions. The higher pitch also allows for a more brilliant sound, one that I find complements the rapid-fire wordplay and playful dialogue that characterise 17th-century drama in general.

This evening’s performance also replicates the size and sound of Cavalli’s instrumental ensembles, as we have understood them through studies of the accounting books of Venetian theatres. Cavalli made small changes to existing scores to suit different singers at the time and we make no apology for doing so again tonight, but no attempt has been made to re-orchestrate and enlarge Cavalli’s musical material, as has been done on questionable grounds in the past.

Lastly, some of the performances that you will see and hear tonight are on instruments (including a beautiful lira da gamba by Ian Watchorn) whose construction has only been made possible by the generosity of Pinchgut supporters. Without them, Pinchgut would not exist, and our adventures with the past, in search of ourselves, would not be possible.

Erin Helyard Musical Director

2] Musical editor's note

Written for performance at the Teatro San Cassiano in Venice during the Carnival season of 1644, L’Ormindo was the third collaboration between the composer Cavalli and his librettist Giovanni Faustini. It never seems to have been revived during Cavalli’s lifetime, and had to wait until 1969 when Raymond Leppard prepared it for his inuential production at Glyndebourne. However, he cut about a third of the opera and deliberately omitted the fact that Ormindo turned out to be Ariadeno’s long-lost son, consequently robbing the plot of much of its ingenuity and driving force.

This new performing edition is based on the single surviving musical source, a 17th-century fair copy of the score housed in the Contarini Collection in Venice, along with a copy of the original libretto in the British Library in London. The copy of the score was probably made at Cavalli’s request late in his life, when he seems to have had all his operas copied professionally. Maybe he was preserving his work for posterity, but whatever his intentions, this unique score gives us the basic material required for a production today.

Regardless of how neat the surviving score is, there are still problems. Scattered throughout the manuscript are gaps: some large, some small, some easily filled in and others just mystifying. The biggest problems appear in the second act. At the end of the act, for example, the duet for Ormindo and Erisbe breaks off half way through. The style of the existing music seems to indicate that this is the first (slow) half of an extended double-section duet which probably broke into something more exultant, reflecting the lovers’ beginning a new and happy life. I have composed an ending to the first half of the duet and then added a second half from Cavalli’s Le Virtù de’ strali d’Amore (The Power of Love’s Arrows, written two years earlier in 1642) which ends the act with a suitably ecstatic flourish.

Other problems include the notorious blank staves: indications of where instrumental accompaniment should be, but the accompa¬niment itself frustratingly absent. For the Ormindo / Erisbe death scene we can fill in these blank staves from Cavalli’s Erismena (Venice, 1655), where he recycled about a third of this duet. Other editorial additions include little pieces of instrumental music to cover scene changes and entrances and exits (all taken from other, roughly contemporary, Cavalli operas) and additional accompani¬ments in situations where Cavalli is know to have added them in similar dramatic circumstances. Hence in Act Three the ‘ghost’ has a string accompaniment, as does Osmano’s reading of Cedige’s letter.

All in all, we know so little documentary evidence regarding opera production in 17th-century Venice that there is no possibility of our recreating exactly what happened in the Cassiano theatre in 1644; and even if we did succeed, how would we recognise the fact that we had achieved our goal? However, if Cavalli walked into City Recital Hall Angel Place, I hope that he would not be too surprised by what he heard, and would recognise it as his own.

Peter Foster © 2009

3] Director's Note

The world of Ormindo is a world in which anything is possible. The challenge facing Adam (the designer) and me was how to transform Angel Place into this world. Trying to beat the space seemed conceited, so the question was how to incorporate it into this magical world of possibilities.

Our first response was to look at where the piece was actually set. Fez is in Morocco, a land that conjures up thoughts of the exotic, of distant shores, of heat hazes and mirages, where the impossible suddenly became possible.

Both Adam and I have travelled quite extensively in these regions, so one starting point was travel albums. These inspired us towards a place that felt and smelt like the world of Ormindo without placing it firmly in one century or another. We decided that the story of Ormindo was a story that was just as comfortable in today’s world as it may have been when it was written: love triangles, older men and younger women, affairs, broken promises, renewed vows and of course a set-up to unravel the truths. So we came to the design as recognisably Middle Eastern without being too specific, intriguing without being mystifying and, most importantly, a landscape that provided us with opportunities to play out this wonderful comedy.

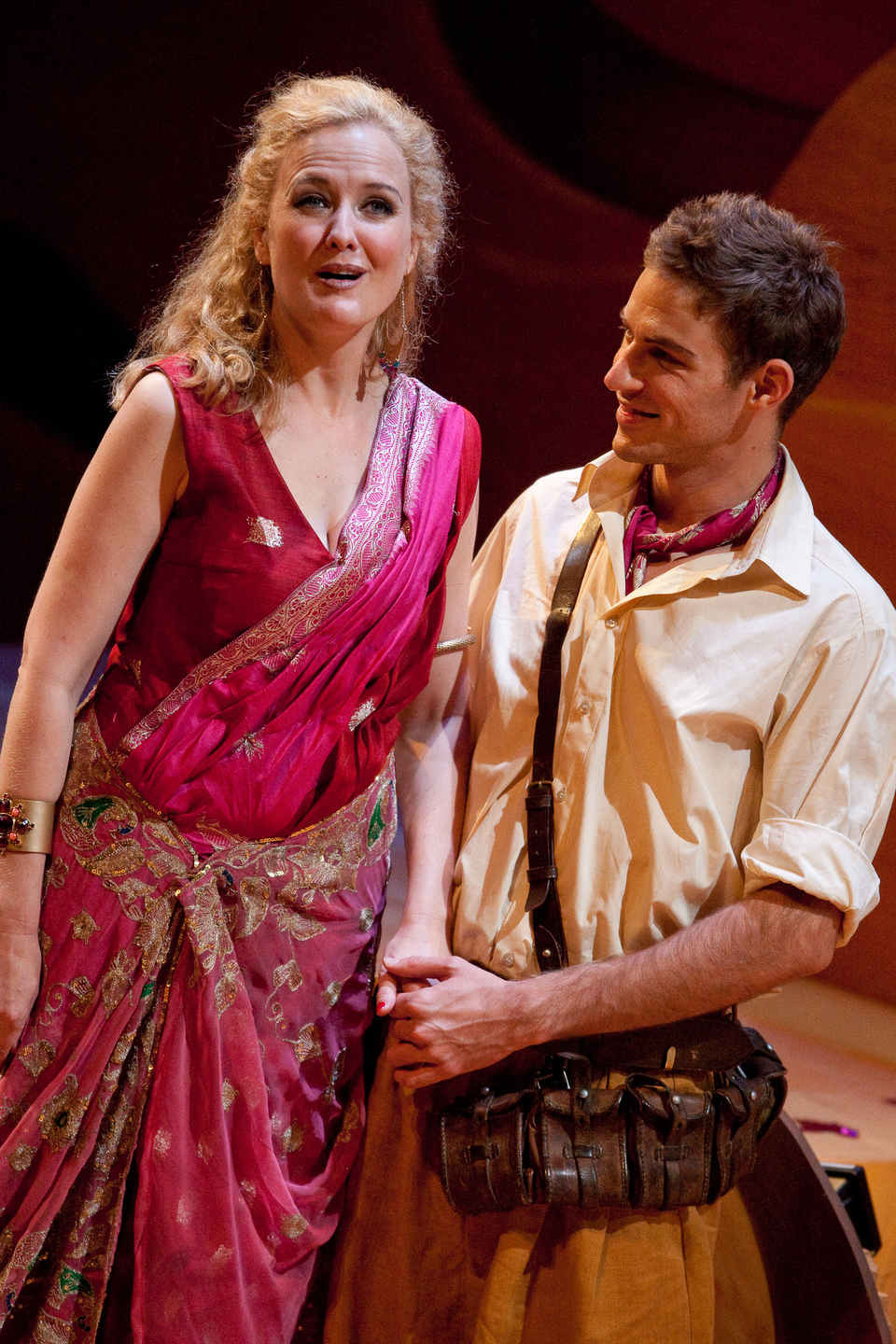

The costumes then reflect this world, and once again they are not meant to be a specifc time or place, but rather anytime. We have made reference to the period in which this piece was written with the inclusion of gold in both the set and costumes. This is more to pay homage to its origins than to fix it in its time. In trying to simplify the relationships of who goes with whom, we devised a colour code: blue for Ormindo’s ‘team’ and red for Amida’s. The women are dressed in the colour of the man they ultimately want to be with.

Dramatically, what is important is not so much who everyone is, but where they end up. In the telling of the story the key aspect is that each character has a single intention; it is then a matter of how they achieve this outcome. Some do it by means of deceit; others do it by means of escape; yet others do it by trickery and magic. In the end, though, they all manage to achieve their desired outcome. Trying to capture the comedy lends itself to situation as much as it does to character. So we have intentionally set up scenes that are ‘theatrical’, making reference to the melodrama but without detracting from the actual story line. Comedy is best played out rather than thought out, so I have tried to keep this part of the opera in the physical, which gives the performers a wonderful chance to show off their comedic timing. Most importantly, it is my intention that the audience will submerge themselves in the heat and heart of this world: that you will suspend your disbelief long enough to enjoy and revel in this wonderful piece of opera, and that in the end, to quote a famous writer, ‘All’s well that ends well!’

Talya Masel © 2009

ARTIST INFORMATION

David Walker Ormindo

Trevor Pichanick Amida

Jane Sheldon Nerillo

Anna Fraser Melide

Kanen Breen Erice

Taryn Fiebig Sicle

Fiona Campbell Erisbe

Anna Fraser Mirinda

Richard Anderson Ariadeno

Andrei Laptev Osmano

Orchestra of the Antipodes – Julia Fredersdorff, leader

Erin Helyard conductor and harpsichord

Talya Masel director

assisted by Mark Gaal & Sean Hall

Adam Gardnir set & costume designer

Bernie Tan-Hays lighting designer

Nicole Dorigo language coach

Deborah Fox repetiteur & continuo

Claire Aristides jewellery designer

Sophie Mackay stage manager

WATCH

Gallery

We acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we work and perform, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation – the first storytellers and singers of songs.

We pay our respects to their elders past and present.

CONTACT

PO Box 291, Strawberry Hills, NSW, 2012, Australia

Ticketing and Customer Service 02 9037 3444 | ticketing@pinchgutopera.com.au

info@pinchgutopera.com.au

© COPYRIGHT 2002 - 2024 PINCHGUT OPERA LTD | Privacy Policy | Accessibility | Website with MOBLE