Dardanus

BY JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU

libretto by Antoine Le Clerc de La Bruére

Nov 30, Dec 3, 4 & 5 2005

City Recital Hall Sydney

Rameau's Dardanus

In setting up a chamber opera company, our artistic directors (and Francophiles) Antony Walker and Erin Helyard desperately wanted to do some French baroque opera, in particular the works of Jean-Philippe Rameau.

Dardanus was the work chosen, and triumphant it was. We had to specially commission some instruments, and we spent a lot of time on the French. We were very fortunate to have the great Paul Agnew in the title role, and our eyes were opened (even further) to the wonders of the score.

Two great arias stand out - Monstre affreux and Lieux funestes, and many wonderful choruses and dances. And fair to say that our audience has requested more French baroque opera every year since then.

REVIEWS

READ

1] Dardanus - Program notes

Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) is generally considered to be one of the most significant French composers of the high baroque era. He is remembered above all for his many theoretical and polemical writings as well as his richly innovative compositions, some of which were the focus of heated debate during his life time. His output earned him an unsurpassed level of honour and praise, and has left an indelible mark in the history of music.

Perhaps one of the most striking facts about Rameau is that he only made a name for himself relatively late in life. In early years he was trained as an organist by his father and he held positions in various centres including Paris, Dijon and Lyons. In 1722, at the age of thirty nine, Rameau settled permanently in Paris. In the same year his ground-breaking Traité de l’harmonie (Treatise or Essay on Harmony) was published, helping to spread his name in the French capital. In spite of this, Rameau found it difficult to procure a post as an organist until 1732. And so, during the 1720s he was forced to make a living primarily by teaching harmony and providing continuo skills, though he also published various collections of compositions including two books of exquisite harpsichord pieces and some cantatas.

It was Rameau’s stage works described variously as ‘tragédies en musique’, ‘opéras’, ‘opera-ballets’ or ‘comédie-ballets’, that were to catapult him to fame and notoriety. His first ‘tragédie en musique’ Hippolyte et Aricie was first performed in 1733 and was followed by several other successful large-scale works including Les Indes galantes (1735), Castor et Pollux (1737), Les fêtes d’Hébé (1739), and Dardanus (1739). During this relatively productive period Rameau gained the financial support of influential patrons including the Prince of Carignan and the extremely wealthy tax collector Alexandre-Jean-Joseph Le Riche de la Pouplinière in whose employ he remained until 1753. Pouplinière’s social events provided Rameau with opportunities to meet other musicians, artists, aristocrats, and important philosophers, writers and infamous figures including Voltaire, Rousseau and Cassanova, some of whom also generously supported Rameau.

Rameau’s overwhelming popularity led, in 1745, to the award of an annual pension by Louis XV King of France, and this honour and security must surely have inspired Rameau to his greatest productivity and success; he produced at least eleven more dramatic works by 1749 including Platée (1745), Pygmalion (1748) and Zoroastre (1749). Thus between the ages of 50 and 66 (quite elderly by eighteenth-century standards) Rameau witnessed at least twenty-five of his operas and ballets performed, a staggering achievement that could not be boasted by any other French composer of the era. The success of his stage works can be measured by the numerous revivals they received throughout the eighteenth century.

It was Rameau’s stage works, particularly his opéras and tragédies produced in the 1730s that created a two-way split between the musical cognoscenti in Paris. One side supported Rameau while the other derided his compositions, accusing him of breaking with the sacrosanct tradition of French opera established by Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687). Lully’s influence and hold on operatic tradition was established during the golden reign of Louis XVs’ great-grandfather, Louis XIV ‘the Sun King’. At his Paris palace – the Louvre, and his country palace – at Versailles, Louis XIV established, during the second half of the seventeenth century, a distinctive genre known as the ‘court ballet’. This was a fairly large-scale staged musical-dramatic work with elaborate costumes and scenery and featured members of the court aristocracy (an ingenious way of keeping the more dangerous members of his court occupied and under his control) together with professional dancers. Louis the XIV himself took part in such productions and was known as a talented dancer. He also established a hierarchical system of music making at court. His some 200 musicians were divided into three institutions namely ‘The Music of the Royal Chapel’, ‘The Music of the Chamber’ and ‘The Music of the Great Stable’, all with varying functions and producing string and wind players and instrument makers of the highest calibre. Already under Louis XIV’s predecessor Louis XIII, a large string ensemble known as the Vingt-quatre Violons du Roi (Twenty-Four Violins of the King) had been established. Further to this, Louis the XIV established in 1648 the Petits Violons (Small Violin Ensemble) and the two groups accompanied all sorts of entertainments including ballets, balls and so on.

Such was the state of music making when Lully became one of Louis XIV’s favourite musicians. With royal support, Lully was able to purchase in 1672 the exclusive right to produce sung drama and created the institution known as the Académie Royale de Musique. By this time, Lully had learned and absorbed operatic styles of both France and Italy and had also produced successful ‘comédies-ballets’, combining opera and ballet. But in order to produce full scale opera he had to take into consideration the expectations of the extremely influential French literary movement, which demanded that poetry and drama be given a high degree if not the most importance on stage. The other imperative was the already existing ballet tradition. With the help of librettist Jean-Phillipe Quinault, Lully devised a new form of opera known as ‘tragédie en musique’ and later ‘tragédie lyrique’, that successfully brought together all these elements.

Quinault’s tragédies were set in five-acts and combined ancient tales or myths, with lighter entertainments or ‘divertissements’ which contained elaborate and colourful dances and choral singing often with no real link to the plot. These divertissements were meant for the amusement of the public. Lully’s supreme talent lay in his ability to represent the grandeur of Louis XIV’s court and reign in the music, through the two-sectioned French overture, the ballet music, spectacular choruses, the adaptation of popular Italian recitative to French style, and the invention of the lyrical and simple ‘air’. He skilfully created dramatic focus by his idiosyncratic mixture of recitative, air and instrumental music. Here, emotions were conveyed by simple means. The type of vocal fireworks that so dominated Italian opera was eradicated and the music became tuneful with simple and understated ornamentation. The drama and declamation of the words became emphasised, while spectacle and sheer entertainment were achieved through the ballets, staging and costumes.

Well into the eighteenth century, many composers emulated Lully’s operatic framework, occasionally adding to it with Italian style arias, or expanding on the entertainments, the harmonic complexity and so on. Rameau was certainly no exception, however while preserving the essence of Lully’s form, he made many changes. Some of these went hand in hand with his theory of harmony; melodies took particular shapes based on the relationship and movement between triads in his newly developed tonal system. And he used a veritable painter’s palette of chords and progressions which were extremely rich and thick in texture and helped create drama and suspense through continual emphasis of dissonance and its release in consonance.

It was such elements that upset Lully’s supporters, who initially found Rameau’s music unnecessarily complicated, difficult to understand, unnatural, rough and even grotesque. In his defence, Rameau made it known in the preface to Les Indes galantes that he had ‘sought to imitate Lully, not as a servile copyist, but in taking, like him, nature herself-so beautiful and so simple-as a model.’ The dispute intensified with the production of each new Rameau opera during the 1730s, but by the 1750s the tide turned and those who had once rejected Rameau fearing that his style would overshadow the music of their revered Lully, came to regard Rameau as the greatest contemporary French composer.

Rameau’s ‘tragédie en musique’ Dardanus was produced at the height of the dispute in 1739 and there were many differing opinions as to the value of the work, most of them it seems were negative. The work was performed 26 times in its first run but achieved only ‘luke-warm’ praise and success despite the enthusiastic actions of the Rameau’s supporters who sought to extend the run by attending in large numbers (about 1000) every night. It would seem that there were indeed some deficiencies in the original version because for its revival in 1744, Rameau and librettist Le Clerc de La Bruère reworked the plot and the opera as a whole. In fact an entirely new plot was devised for the last three acts and the 1744 edition described the work as a new ‘tragédie’. There is little to inform of the works success in the revised form but by 1760, when Dardenus was revived yet again, it was generally considered to be among the finest of Rameau’s stage works.

Pinchgut Opera’s production of Dardanus is based primarily on the original 1739 version with some additions from the 1744 version notably the superb and unforgettable prison scene ‘Lieux funestes’ in Act IV Scene 1. This is written in the form of a monologue, to which Rameau added an extraordinary bassoon obligato. The piece also contains sequences of chromatic harmonies and bitter dissonances that cannot be found in his other works. The choice of which version to use for a revival of Dardanus is tricky. Certainly, in the 1744 version there is an increase in dramatic suspense and emotion between the main protagonists, but in order to achieve that other features are suppressed. Ironically, a contemporary criticism of the 1739 version indirectly points to its great value. One journalist noted that ‘people were struck by the harmonic richness but there is so much music that in three whole hours the orchestra didn’t have time so much as to sneeze.’ No-doubt Rameau took this to heart because the 1744 version omits some of the most outstanding movements and modifies and reduces others to the extent that the music suffers greatly. As historian Graham Sadler has put it, ‘the fact remains that the original 1739 version of Dardanus is, in purely musical terms, one of Rameau’s most powerful and inspired creations.’ And to safeguard against an overly lengthy modern revival, Pinchgut has made one other significant change. The original Prologue, which largely sets a scene unrelated to the main plot, has been omitted.

Dardanus contains many memorable scenes and music including two ceremonial divertissments in Acts 1 and 2. Here, airs, choruses and dances are arranged according to the custom in France at the time. But unlike other contemporary operas, these and other divertissements relate to and extend the plot. In the Act 3 celebrations after Dardanus has been captured, Rameau includes several inventive movements including a reworking for duet and chorus of his fabulously bubbly harpsichord piece Les Niais de Sologne (1724). This is shockingly contrasted with the appearance of the sea monster, a sudden twist in the plot which was the type of standard rhetorical device used by French librettists of the era. Act 4 produces the sublime dream sequence with a trio and chorus ‘Par un sommeil agréable’. The memorably haunting nature of this scene has led the English Rameau specialist Cuthbert Girdlestone to remark that it is ‘at once an inducement to sleep, a berceuse and an impression of the state of sleep’. In other vocal numbers Rameau creates high tension and tortured feelings with anguished dissonances and falling or sighing appoggiatura-like figures.

The ballet music in Dardanus is also stunning. There are some 30 dance movements all rich with harmonic invention, extraordinary melodies and masterful orchestration. The Menuets, Tambourins and particularly the Act 5 Chaconne demonstrate Rameau’s supreme resourcefulness as a composer.

Rameau was described by many contemporaries as the composer of Dardanus. Yet in modern times Dardanus has rarely been performed. Girdlestone was of the opinion that ‘Dardanus is a musician’s opera, and operas that appeal only to musicians remain within their scores where not even musicians often seek them out’. There may be some truth in this, however, the sheer freshness and inventiveness of Rameau’s score cannot but appeal to modern audiences who have been starved of this wonderfully suave French style. Rameau’s music and Dardanus in particular provides a special glimpse of the eighteenth century which cannot be viewed elsewhere.

© Neal Peres Da Costa 2005

2] Synopsis

Act One

Iphise, daughter of King Teucer of Phrygia, is secretly in love with Dardanus, her father’s enemy. Dardanus, the son of Jupiter, loves her also, but each is unaware of the other’s feelings. Iphise knows her duty and tries to forget Dardanus. Teucer enters with news of a military alliance for Phrygia: Anténor will fight for them against Dardanus, and in return will be given Iphise as his bride. Teucer and Anténor take an oath of allegiance on the tombs of fallen warriors. Joined by the Phrygian warriors, the new allies pray for the gods' aid.

Act Two

Dardanus comes to the grove of the seer Isménor, confessing his love for Iphise and seeking his guidance. Isménor promises to help him, giving him an enchanted cloak which enables him to appear as Isménor. When Anténor and Iphise, one after the other, come to Isménor for advice, it is Dardanus, wearing the cloak, who hears their secrets. Anténor is worried at Iphise's coldness, and fears he may have a rival. Iphise has come to plead with Isménor to rid her of her love for her father's enemy. Dardanus, overjoyed to learn that his feelings are returned, removes the disguise and declares his love for Iphise. He is taken prisoner by the Phrygian guards.

Act Three

The Phrygians celebrate the capture of Dardanus. But the festivities are interrupted by the news that Neptune has sent a monster from the sea as punishment for imprisoning a son of Jupiter. Anténor decides to fight the monster, protect Phrygia, and win Iphise’s affection.

Act Four

Dardanus is in prison. Vénus appears, and through a dream persuades Dardanus to fight the sea monster himself. When he awakes he finds himself in the monster’s lair: Anténor has been overcome, but Dardanus slays the beast and saves his enemy’s life. Anténor, not recognising his rescuer, gives him his sword and swears to give him anything he asks, by way of reward. Dardanus asks him to allow Iphise to marry whomever she wishes. Anténor, in despair, refuses.

Act Five

Teucer and the Phrygians welcome Anténor as the slayer of the monster. Teucer gives Iphise’s hand to Anténor in reward. Dardanus appears with Anténor’s sword; Anténor, realising that Dardanus is the one who killed the monster and saved his life, honours his promise. Vénus is triumphant, and everyone celebrates the union of Dardanus and Iphise.

3] Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau lived a long life. Born in Dijon in 1683, he died at age 81 in Paris on 12 September 1764. His life overlapped those of Bach (1685-1750), Handel (1685-1759), Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) and Telemann (1681-1767). Rameau has been described by a contemporary as having ‘a sharp chin, no stomach, flutes for legs’. He was extremely tall and thin; ‘more like a ghost than a man,’ recorded another. His father was an organist in Dijon, his mother a member of the lesser nobility.

Not much is known about Rameau’s early life. At 18 (1702) he was sent to Italy to study music but got no further than Milan. What he did there is not known but it seems he returned to France within a few months. Church records show him popping up in several places in France over the next 20 years, mostly as an organist on short-term contracts. The next confirmed sighting was in 1709 where he succeeded his father at Notre Dame Cathedral but he was gone from there by 1713 because in that year the city of Lyon was about to celebrate the Treaty of Utrecht: Jean-Philippe Rameau was appointed Musical Director for the ceremonies but the musical element was cancelled and the money given to the poor.

Rameau continued his nomadic wanderings between 1713 and the early 1720s. He appeared in Dijon, Clermont and Lyon, sometimes signing long-term contracts as an organist and failing to honour them. A story about his escape from a contract at Clermont Cathedral has him composing a mass so awful that the chapter conceded that they could not keep a composer who wanted to leave. In this period, though, he wrote his Traité de l’harmonie and Nouveau système de musique théorique. There are published keyboard works and cantatas from this time but he became known as a theoretician before he was recognised as a composer. By 1724 he was in Paris and, it seems, he never left. The following year two Louisiana Indians were ‘displayed’ in a theatre and Rameau wrote music to accompany their dances: Les Sauvages.

In 1726, at age 42, Rameau married Marie-Louise Mangot. She was 19 and the daughter of a family of musicians, originally from Lyon. It seems to have been a happy marriage and produced four children, of whom one boy and one girl survived their father. Rameau continued his theoretical writings and worked as a jobbing organist – there is no record of any fixed appointment anywhere – and teacher.

Opera appears in his résumé in the early 1730s. The first work composed was Samson – a tragédie en musique for which the libretto (still in existence) was written by Voltaire. The music can be dated at 1733 but was unpublished, censored, unperformed and lost. Somewhere around then Rameau met Le Riche de la Pouplinière, a wealthy man who was to become his patron. Hippolyte et Aricie was the first product of this patronage. It was performed privately in 1733 in La Pouplinière’s house with his singers and orchestra, and on 1 October that year, just after Rameau’s 50th birthday, the opera was performed at the Paris Opera. The work created a storm. Lully was the gold standard for French opera and the Lullists were very unhappy about any departure from his rules. In 1749 Rameau wrote Naïs, a pastorale héroïque to celebrate the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle (ending the War of the Austrian Succession). In England Handel was composing the Royal Fireworks Music for similar celebrations.

Rameau continued to live as part of La Pouplinière’s household and for several periods he and his family lived in apartments in his patron’s house. He continued to compose operas and opera-ballets and to write musicological works. Dardanus was the product of 1738-39. At the first performances (there were 26 initially) the reception was cool. The reservations were not, it seems, about the music but the plot and poetry. Rameau sought help from another poet and a revised version was presented in 1744. This was better received. (Our production is an amalgam of the best parts, musically, from the two versions.) It was revived in 1760 and again, after Rameau’s death, in 1768 and 1771. After that, performances were few and infrequent. The French public fell for Italian opera buffa and all but forgot their own geniuses for a couple of hundred years.

More operas and opera-ballets by Rameau followed after Dardanus: Platée (1745), Zoroastre (1749) and Les Paladins (1760). All were well received, except by the Lullist traditionalists. Rameau also continued theoretical writings. He wanted to be famous for these, more than for his music. Late in life he said he regretted the time spent composing, as that had taken time he could have spent writing.

This was the Age of Reason and Rameau, a friend of Rousseau, believed harmony could be reduced to mathematical rules. He sent one of his papers to Johann Bernoulli (a Swiss mathematician, brother of the more famous Jacob Bernoulli, whose theories on fluid dynamics became the basis of the aerofoil), seeking and receiving his seal of scientific approval.

Towards the end of his life Rameau found his creative powers weakening but his reasoning powers remained. He continued to write and just four months before his death he was ennobled by the Emperor. He seems to have had good health throughout his life until the fever from which he died on 12 September 1764. He was buried in St Eustache, near Les Halles. The precise site in the church is unknown though there is a fairly modern plaque to his memory in one of the chapels. By this time, Rameau’s fame ensured a send-off with great ceremony. Three memorial services were held in Paris and others throughout France. His widow lived until 1785 but nothing is known of his descendants.

Some described Rameau as mean, bad tempered, unapproachable and unsociable. But he had enemies and perhaps these were judgments coloured by disagreements. One story perhaps gives greater insight into his character. Michel-Paul-Gui de Chabanon, a young friend (later a member of Académie Française, occupying the seat subsequently taken by Victor Hugo), saw him at a performance of his Castor et Pollux at Fontainebleau not long before his death. Chabanon records:

‘I ran towards him to embrace him; he started abruptly to take flight and came back only on hearing my name. Then, excusing the weirdness of his welcome, he said he avoided compliments because they embarrassed him and he never knew how to reply.’

© Ken Nielsen 2005

ARTIST INFORMATION

Paul Agnew Dardanus

Paul Whelan Anténor

Kathryn McCusker Iphise

Stephen Bennett Teucer

Damian Whiteley Isménor, Un Songe

Penelope Mills Vénus

Miriam Allan Une Phrygienne, Un Songe

Anna Fraser Une Phrygienne

David Greco Un Phrygien

Dan Walker Un Songe

Corin Bone Un Songe

Cantillation, chorus

Orchestra of the Antipodes – Rachael Beesley, leader

Antony Walker conductor

Justin Way director

Hamish Peters designer

Bernie Tan

lighting designer

Edith Podesta choreographer

Nicole Dorigo language coach

Ali Aitken & Roger Press stage managers

LISTEN

Maras, Bellone ...

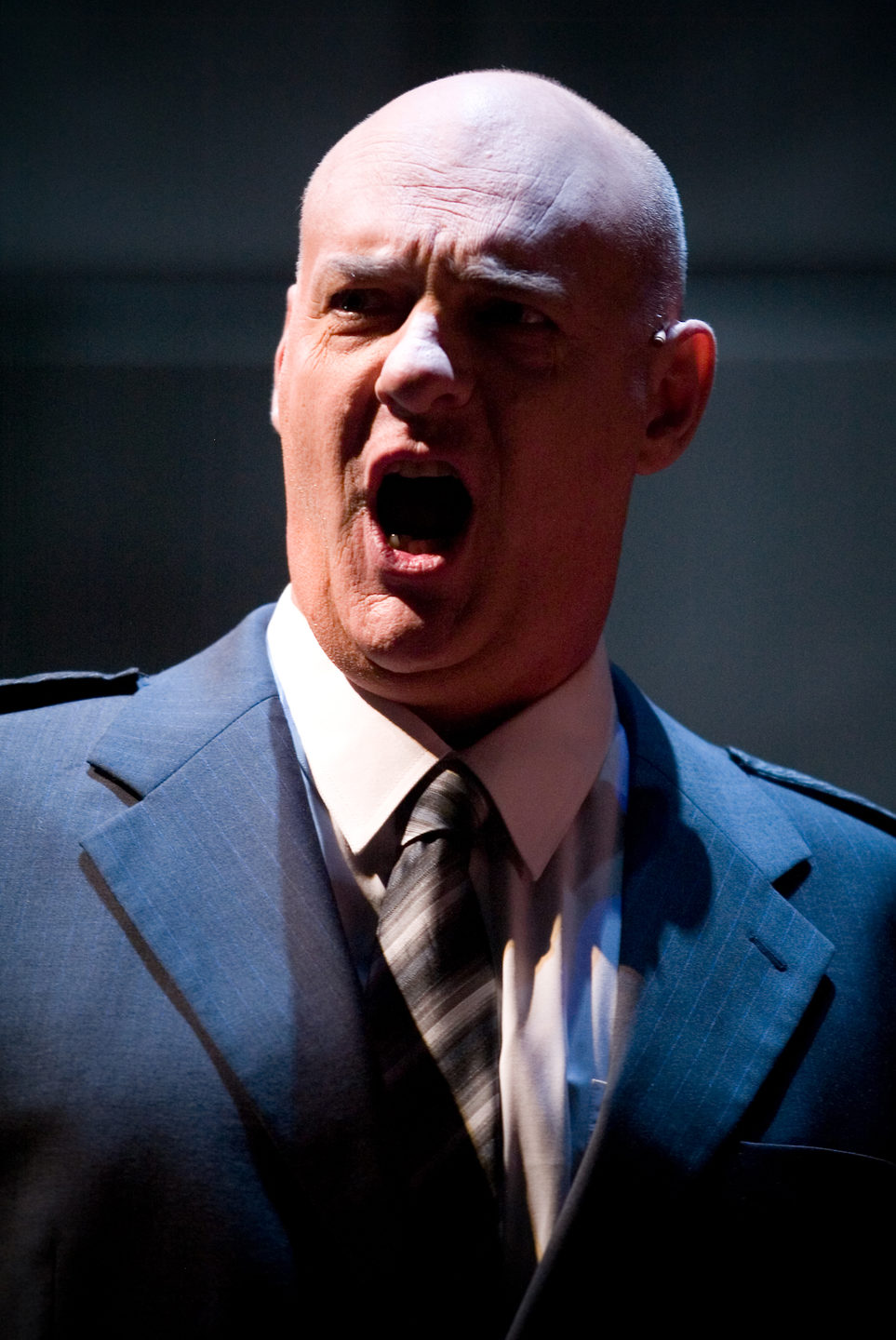

Who knew 17th Century French music could be this brutal and thrilling? Anténor (Paul Whelan), Teucer (Stephen Bennett) and the people request the assistance of the gods of war.

Paul Whelan, Stephen Bennett, Cantillation, Orchestra of the Antipodes, Antony Walker conductor.

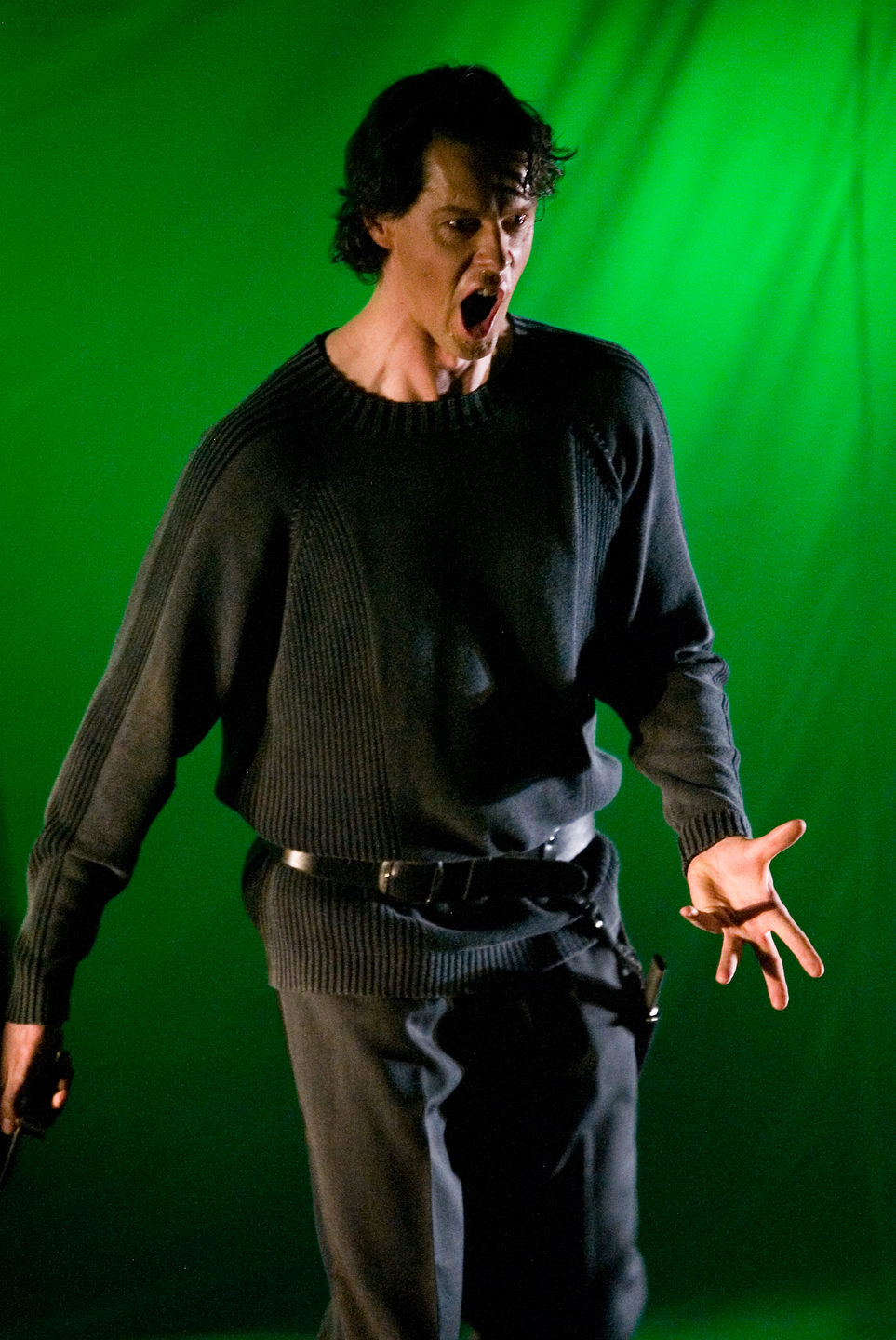

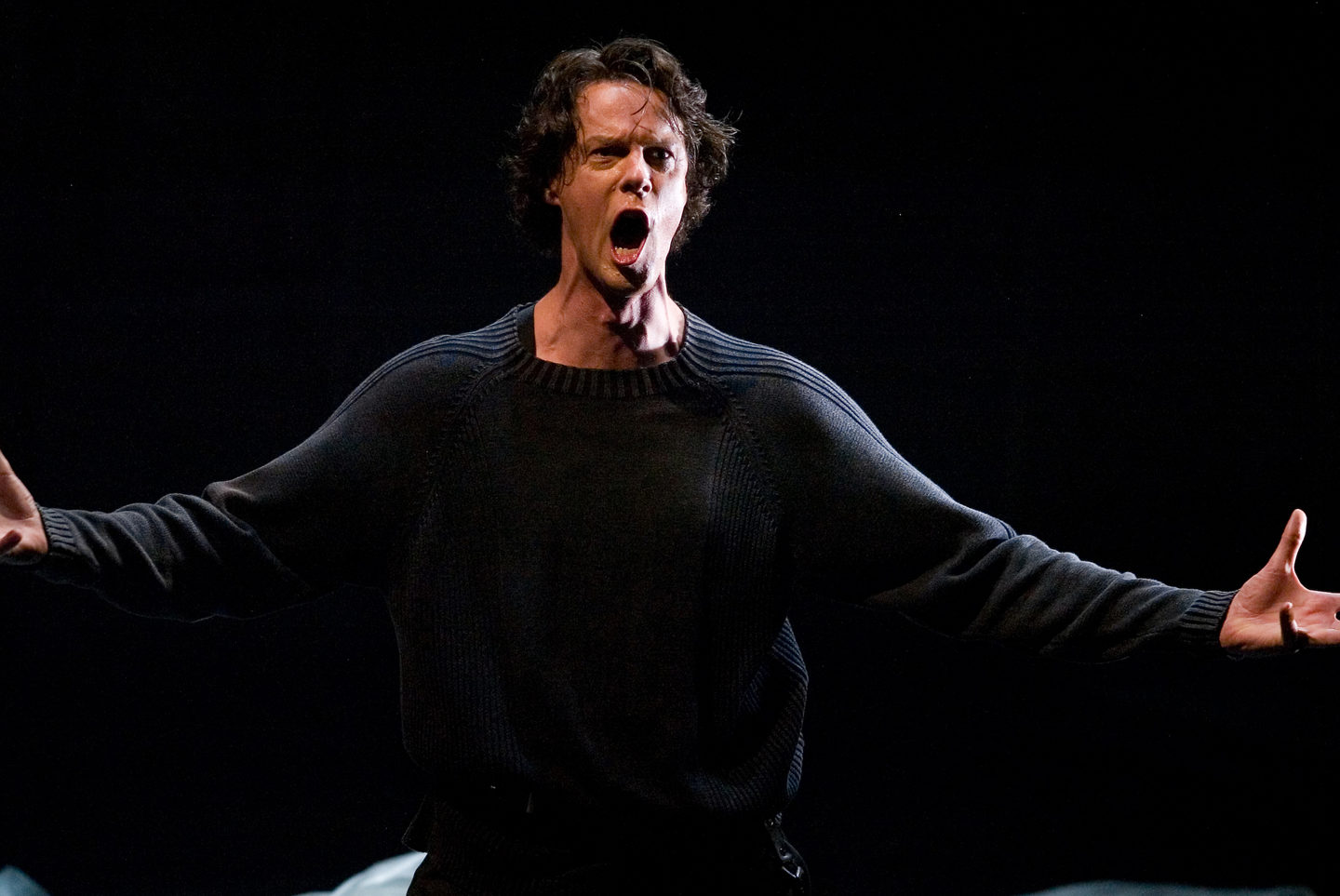

Lieux funestes

Possibly the most famous French baroque aria, Dardanus (Paul Agnew) sings this lament from his prison cell.

Paul Agnew, Orchestra of the Antipodes, Antony Walker conductor.

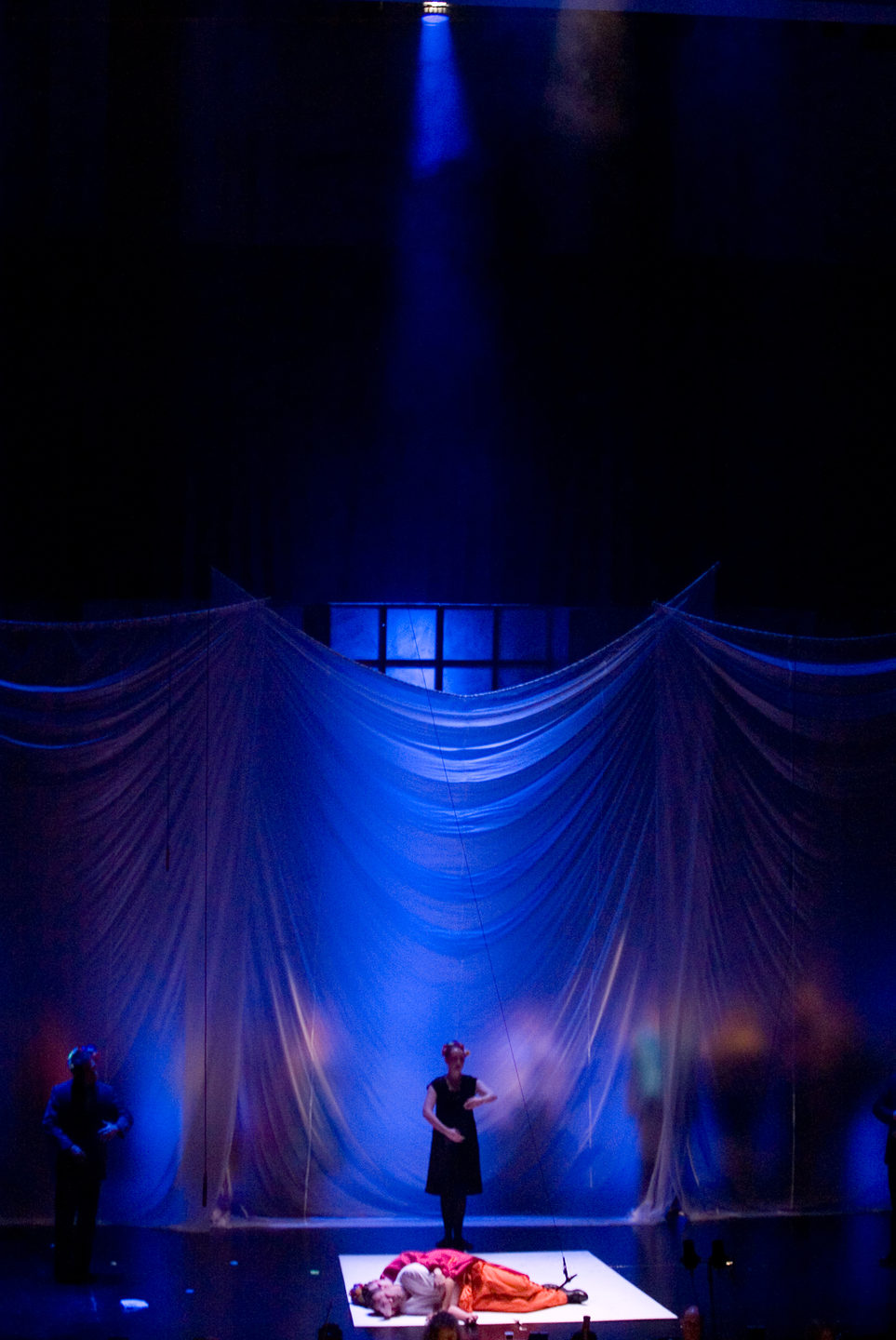

Par un Sommeil Agreable

The Dreams appear in Dardanus' prison cell and give him the gift of peaceful sleep, promising love.

Miriam Allan, Dan Walker, Corin Bone, Cantillation, Orchestra of the Antipodes, Antony Walker conductor.

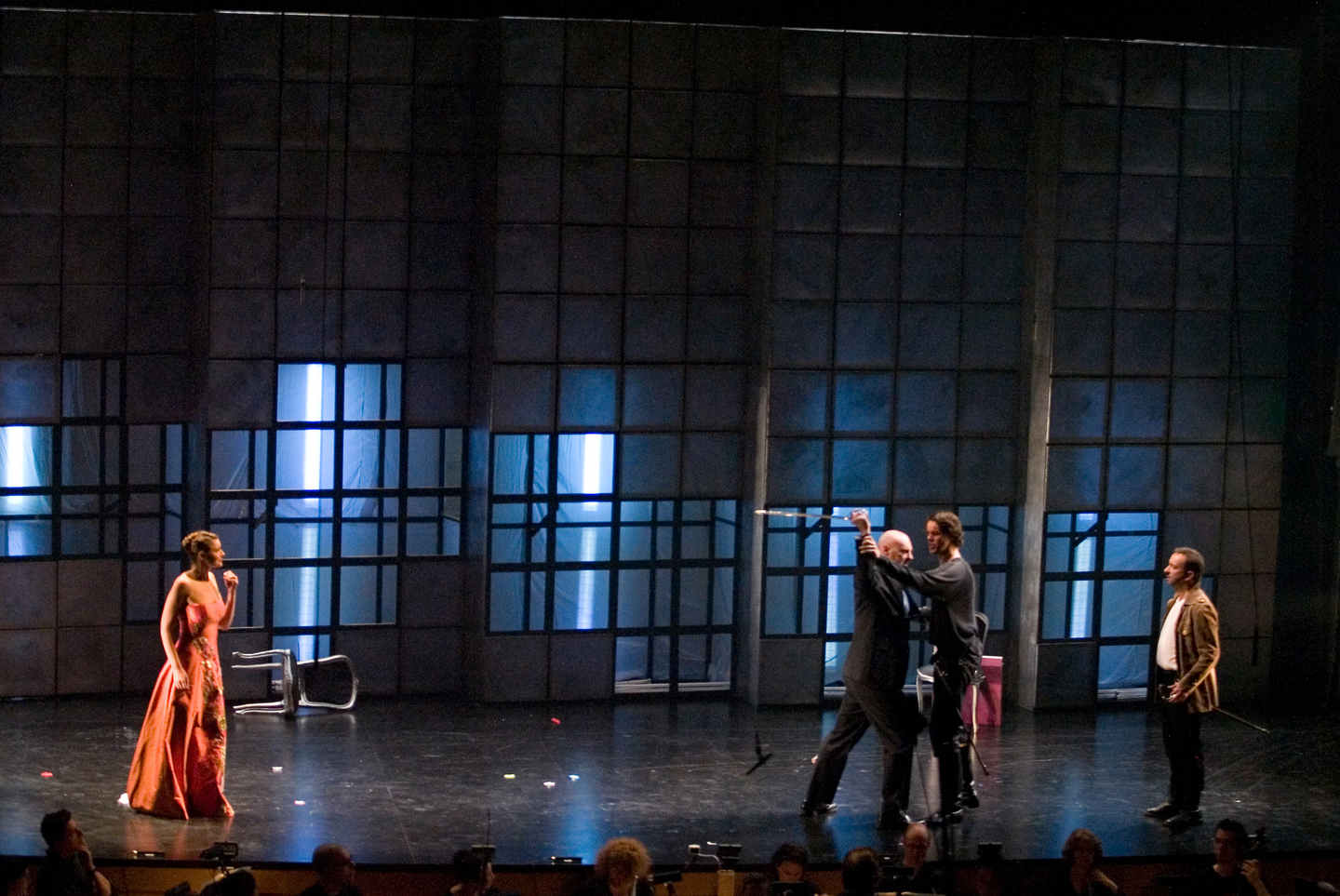

Gallery

We acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we work and perform, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation – the first storytellers and singers of songs.

We pay our respects to their elders past and present.

CONTACT

PO Box 291, Strawberry Hills, NSW, 2012, Australia

Ticketing and Customer Service 02 9037 3444

ticketing@pinchgutopera.com.au

info@pinchgutopera.com.au

© COPYRIGHT 2002 - 2025 PINCHGUT OPERA LTD | Privacy Policy | Accessibility | Website with MOBLE