L'Anima del Filosofo

by Joseph Haydn

libretto by Carlo Francesco Badini

Dec 2, 4, 5 & 7 2010

City Recital Hall Sydney

Hayden's L'Anima del Filosofo

Haydn's great masterpiece and last opera L'anima del filosofo (or the Soul of the Philosopher) was never performed in his lifetime. Haydn travelled to London in 1790 where he had been commissioned to write several symphonies, and this opera. Due to a dispute between the theatre and King George III the opera was never performed. In fact the first ever performance was in 1951 with Maria Callas and Boris Christoff!

A re-telling of the Orpheus story, this opera contains much amazing music with a remarkable storm scene with its very lifelike depiction of the forces of nature. There is no happy ending with Orpheus torn apart by the Maenads. Soprano Elena Xanthoudakis takes on the challenging task of singing both Euridice and the Genio, with brilliancy and beauty.

REVIEWS

READ

1] ‘Orfeo for England’: Haydn’s Last Opera

It is no accident that, since the beginning of opera in the late 16th century, composers and librettists have been drawn to the Orpheus myth. For two centuries he was viewed as the consummate and archetypal musician whose supreme eloquence embodied the persuasive agenda of music itself. Heralding from Thrace, a country renowned for its singers, he was said to be the greatest son of Apollo, the god of light, sun and the arts. For Pindar, Orpheus was the ‘father of song’. His affective power as a singer was so great that he could calm beasts and men; even the sea itself. He is often shown in Greek art accompanying himself on the kithara, the lute-like instrument of the time.

For composers like Monteverdi and Peri, the Orpheus myth was the ideal vehicle to promote their new innovation, sung drama. The fact that Orpheus was a singer helped rationalise the strange notion that people were singing on a stage, rather than reciting or acting. One feature that distinguishes all the Orpheus operas is a ‘song-within-an-opera’, where Orpheus is represented on stage as actually singing a song.

When judged within the spectacular and meteoric career of Haydn, therefore, no better theme could have matched the extraordinary reception accorded him in London during his first sojourn there in 1791. English poets lauded Haydn as the ‘Orpheus of his age’ and his arrival there had been long anticipated. London in the 1790s was one of the most prosperous and politically stable cities in Europe. The upper and middle classes were gripped with what was contemporaneously called ‘a rage for music’ and its concert rooms and halls, musical gardens and opera houses were filled with an excited and engaged public, eager to hear and judge the latest music. The rise of the modern practice of purchasing tickets and attending publicly advertised concerts arose first in 18th-century England. So too did the now familiar plan of the concert hall, with its continuing tradition of fixed benches focally oriented towards a raised stage.

London impresarios had been trying since the 1780s to entice popular composers like Mozart and Haydn, but only one eventually succeeded: Johann Peter Salomon, a German violinist, composer and entrepreneur. He came to Vienna and his famous first words to Haydn were: ‘I am Salomon from London and have come to fetch you. Tomorrow we shall conclude an agreement.’ His timing was perfect: Haydn’s great patron, Prince Nikolaus Esterházy, had died just a few months earlier, and the subsequent disbanding of the court orchestra under his successor Prince Anton had freed Haydn from courtly duties.

Haydn arrived on New Year’s Day, 1791. He later wrote that he was proud that he had not vomited on the rough sea crossing, but noted: ‘I needed 2 days to recover.’ Haydn was fêted, dined, toasted and applauded everywhere he went, to his great delight and occasional consternation. ‘My arrival caused a great sensation throughout the whole city ... everyone wants to know me. I had to dine out 6 times up to now, and if I wanted, I could dine out every day; but first I must consider my health, and second my work.’

Haydn’s contract with Salomon called for the composition of six symphonies and an opera, with funds for the latter coming from Sir John Gallini’s opera company at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket (now Her Majesty’s Theatre). Eight days after arriving, Haydn wrote to Prince Anton back in Vienna:

‘The new opera libretto which I am to compose is entitled Orfeo, in 5 acts, but I shall not receive it for a few days. It is supposed to be entirely different from that of Gluck. The prima donna is called Madame Lops from Munich – she is a pupil of the famous Mingotti… Primo homo is the celebrated Davide. The opera contains only 3 persons, viz. Madam Lops, Davide, and a castrato [in the role of the oracle Genio], who is not supposed to be anything special. Incidentally, the opera is supposed to contain many choruses, ballets and a lot of big changes of scenery…’

When Haydn received the libretto, by Carlo Francesco Badini (c.1710–c.1795), an Italian emigré notorious for his scurrilous newspaper gossip, he discovered that there was a fourth role: Creonte, the father of Eurydice.

Gallini had taken great pains to appoint superb singers with international reputations, but Haydn wrote in March to his mistress that Madame Lops was ‘a silly goose’. Before Haydn could begin to remedy the situation (Haydn and Mozart’s friend, the great Nancy Storace, for example, would have made an ideal replacement), scandal descended. The King’s Theatre, freshly rebuilt after an arson attack, lacked only one thing: a licence from King and parliament to stage Italian opera. The Lord Chamberlain was a supporter of the Pantheon theatre in Oxford Street, and was in no hurry to issue a licence to its rival. Consequently the company at the King’s Theatre had to skirt the law and present operas and entertainments as ‘rehearsals’ without scenery, staging, lighting or costumes.

Haydn continued to work on his ‘Orfeo for England’, as he named it himself in his list of works, even when it was clear that it would not be staged – probably gambling on a concert version, as had been done with Paisiello’s Pirro, which had been performed there to great success in February and March. But negotiations faltered as the Lord Chamberlain continued to refuse to act, and so Haydn’s work was set aside before it even reached rehearsal stage. (The King’s Theatre would finally present legal opera in 1793, whereas the Pantheon would in turn burn to the ground in an arson attack in 1792.)

Of all the Orpheus operas in the 18th century, Badini’s libretto keeps most closely to the story’s Ovidian roots. Aristaeus’ attempted rape of Eurydice brings about events that lead to her first death, and at the apocalyptic close, Orpheus renounces the love of women before being poisoned by the wild Bacchantes. They tear him limb from limb, a storm arises and a flood carries Orpheus’ body off to rest on the isle of Lesbos.

The title of the opera – L’anima del filosofo – refers to what some scholars have called Badini’s ‘chilly rationalism’. Far from the humanised reading of Gluck’s familiar setting, Badini’s libretto and Haydn’s music outline the gulf between reason and passion in a bleak, almost nihilistic, fashion. Consider the chaotic finale of the final act and its terrifying pianissimo conclusion, the weeping choruses of Eurydice’s funeral, the menacing cackling of the frenzied Bacchantes as well as the gasping, virtuosic solo arias of both Eurydice and Orpheus, both in terror for their lives and their loves. While it is true that Haydn would most probably have altered the work in the usual way once rehearsals began, what remains is one of the great monuments to late 18th-century opera seria.

Self-consciously modern and radically different from other settings of the myth, L’anima del filosofo treads some of the darker paths that Enlightenment thought had opened up. Questions are raised that are not answered and events unfold over which the protagonists have frighteningly little control. Although Haydn’s last opera was never to be staged in his lifetime, the fact that he carefully entered it in his list of works (which rarely included unfinished compositions) shows that he viewed it as a legitimate culmination of his extensive operatic career. Indeed, publications of selections of the opera in 1808 led the reviewer to remark with some surprise that some ‘of the pieces here presented belong quite certainly to the most beautiful things for voice Haydn has ever written.’

Erin Helyard © 2010

2] Synopsis

ACT ONE

Scene 1

Eurydice is alone and distraught in the forest. She loves the musician Orpheus but her father, King Creon, has betrothed her to the beekeeper Aristaeus. The Chorus advises Eurydice to leave the gloom of the forest but she resists. Wild shepherds appear, intending to sacrifice Eurydice to the Furies. The Chorus calls for Orpheus and he arrives. Orpheus charms the shepherds with his music, thereby freeing Eurydice.

Scene 2

In Creon’s palace, his assistants assure him that Eurydice is found and safe. They relay to Creon the events that took place in the forest. Creon decides that although he had promised Eurydice to Aristaeus, fate has intervened and dictates otherwise.

Scene 3

As they can now be married, Eurydice and Orpheus rejoice: ‘Neither fate, nor death, can change my love…’

ACT TWO

Scene 1

Cupids surround Orpheus and Eurydice as they celebrate their union. A suspicious sound disturbs them and Orpheus leaves to investigate it. The Chorus reminds Eurydice of her father’s pledge to marry her to Aristaeus. Aristaeus’ followers arrive and as Eurydice attempts to flee, a snake bites her. Orpheus returns to find Eurydice dead. As Orpheus cradles her in his arms, he accuses Fate of being barbarous.

Scene 2

A messenger informs Creon of Eurydice’s death. Creon swears to avenge his daughter.

INTERVAL

ACT THREE

Scene 1

Orpheus and Creon are at Eurydice’s grave; the Chorus too mourns. Orpheus calls to Eurydice: ‘Beautiful soul, you have flown to heaven, bearing on your wings my hopes and my consolation.’

Scene 2

An aide tells Creon that Orpheus is losing his mind. Creon acknowledges that ‘Whoever loses his beloved, loses himself.’

Scene 3

Orpheus seeks the counsel of the ancient prophet, the Sybil. She tells him that if he wishes to see Eurydice again, he must arm himself with courage and follow her to the underworld. She advises Orpheus to seek consolation in philosophy: ‘It is an enchantment that brings forgetting.’

ACT FOUR

Scene 1

On the banks of Lethe, a river of the Underworld, the Undead menace Orpheus with their misery. The Sybil impels Orpheus forward, to the ferryman Charon; the Furies haunt them as they go.

Scene 2

Orpheus and the Sybil arrive at the gates of Pluto, God of the Underworld. Orpheus begs for, and is granted, entry.

Scene 3

The souls of the Worthy, including Eurydice, languish on the Elysian Fields. The Chorus notifies Orpheus that, should he look at Eurydice, he will lose her forever. Eurydice, limping from her wound, approaches. The Sybil cautions Orpheus to control his desires. Eurydice calls to Orpheus; he looks to her – and loses her a second time. The Sybil too leaves him, calling, ‘You are lost; I must abandon you.’

Scene 4

Orpheus grieves: ‘Hell is in my heart,’ and he calls to the stars: ‘Why suffering; such great cruelty?’ As Orpheus weeps, a group of Bacchantes, followers of Bacchus, God of Wine and Intoxication, arrive and challenge him to forego sorrow and to seek out pleasure. Orpheus rejects their advances. The Bacchantes then force Orpheus to drink ‘the nectar of love’. He dies, poisoned by their potion. As the Bacchantes make their way to the ‘island of delights’, a violent storm erupts and they perish.

3] An approach to Haydn's Orpheus

‘There was an Orpheus before me, and there will be one after me.’

– Marcel Camus, Orfeu negro

The myth of Orpheus and Eurydice has inspired storytellers stretching from the ancients to contemporaries such as Christopher Nolan and his film Inception. Ironically, while we know of them as lovers, Orpheus and Eurydice are eternally linked by virtue of their separation; they are never really together.

Drawing on key elements from the stories by Ovid and Virgil, Haydn and librettist Badini have created a unique version. In titling their opera L’anima del filosofo or ‘The soul of the philosopher’, they place emphasis on the spiritual and personal, something that provides the springboard for our production.

The balance of their narrative elements is different from any other musical version: Eurydice is given a father, Creon, a man of learning, who has promised her to the beekeeper Aristaeus. Preferring Orpheus the musician, a man of art, to Aristaeus, the man of industry, Eurydice is torn apart first by her father’s plans and then by Orpheus, who despite his proclamations appears to be more drawn to music than to her.

The lovers are destined to remain separated: Eurydice is taken by a fatal snakebite. Lost in grief, Orpheus withdraws from the everyday world, composing a prison of guilt and memory. In desperation, he takes his art into the underworld and attempts in vain to challenge the Gods. Our production journeys inward to the artist’s soul, where both the music for which Orpheus lives, and the memory of Eurydice, serve to simultaneously sustain and destroy him.

Two worlds are embodied on stage at the same time: one is a forest of the mind, a place where Orpheus is haunted and propelled by sounds and voices; the other, the realm of the Gods, where, according to their whims, the Fates follow the footsteps of Orpheus and Eurydice and direct the consequences of their actions. Gradually one world penetrates the other.

In a battle between reason and emotion, for Orpheus – unlike Creon, who has also suffered a loss – even philosophy fails to console.

‘The truth of a myth is not in its words but its patterns.’

– David Mitchell, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet

Mark Gaal Director

ARTIST INFORMATION

Elena Xanthoudakis Euridice/Genio

Andrew Goodwin Orfeo

Derek Welton Creonte

Craig Everingham Pluto

Sean Hall actor

Nicholas Gell actor/NIDA secondment

Jake Speer actor/NIDA secondment

Cantillation, chorus

Orchestra of the Antipodes – Alice Evans, leader

Antony Walker conductor

Mark Gaal director

Brad Clark

& Alexandra Sommer designers

Bernie Tan-Hays lighting designer

Erin Helyard assistant conductor

Sean Hall assistant director

Nicole Dorigo language coach

Sophie Mackay stage manager

WATCH

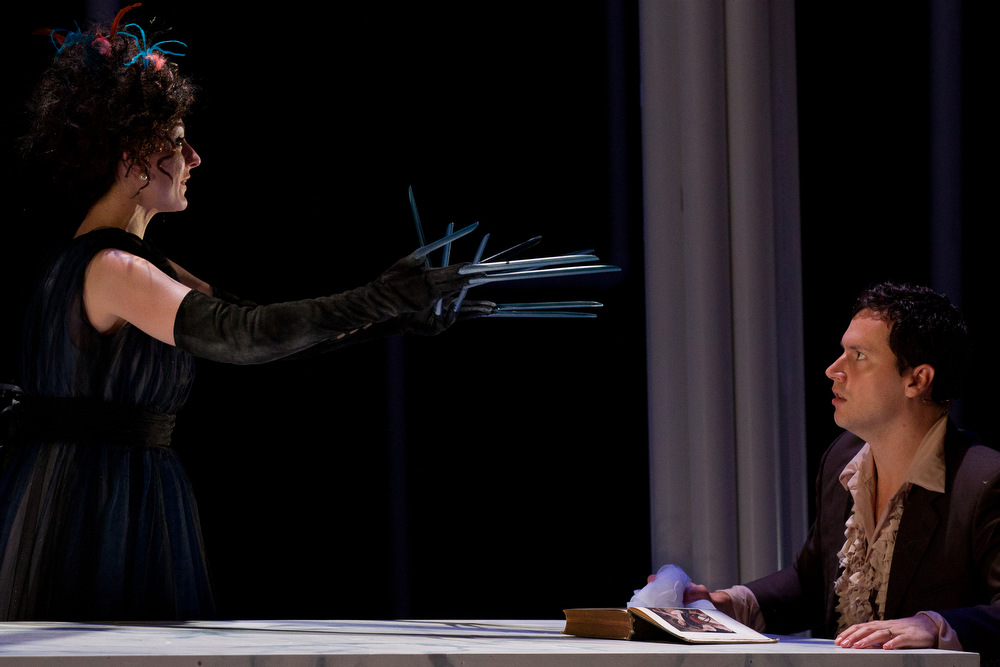

A highlight clip of L'Anima del Filosofo

Gallery

We acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we work and perform, the Gadigal people of the Eora nation – the first storytellers and singers of songs.

We pay our respects to their elders past and present.

CONTACT

PO Box 291, Strawberry Hills, NSW, 2012, Australia

Ticketing and Customer Service 02 9037 3444

ticketing@pinchgutopera.com.au

info@pinchgutopera.com.au

© COPYRIGHT 2002 - 2025 PINCHGUT OPERA LTD | Privacy Policy | Accessibility | Website with MOBLE